The Comedy of Being Human: Interview with Directors

For the first time in forever, WILDe is giving up its classic winter play concept for a split bill: three short plays for the price of one! This March 2026 (not technically winter, but let’s not dwell on that), we present The Comedy of Being Human: an evening of three short plays by world-renowned American playwrights David Ives and Christopher Durang.

Through wildly different stories, this comedy-filled night explores familiar questions: what does it mean to be human? How do we love, dream, and occasionally lose complete control?

The programme brings together three delightfully contrasting comedies. Mere Mortals offers a soulful construction-worker confessional, Soap Opera tells the lightly unhinged story of someone falling in love with a washing machine, and The Actor’s Nightmare delivers an absurdist tale of an accountant suddenly thrust into a leading role.

We sat down with the directors of Soap Opera and The Actor’s Nightmare, who generously took time out of their busy schedules to share more about the rehearsal process - and why you definitely shouldn’t miss this show.

SOAP OPERA

Placed in the middle of the program, Soap Opera is certainly not the average show.

Written by world-renowned playwright David Ives, Soap Opera is a story about love: a very special kind of love. When a washing machine repairman falls for the machine he’s meant to fix, an absurd yet heartfelt romance unfolds. This show is perfect for anyone who has ever had a love-hate relationship with doing laundry, despised the typical stepsister trope or simply enjoyed playing Date Everything (if the play evokes a certain feeling in you, you should definitely check it out).

El, the director putting together the rowdy romance, is sharing a few words about what it’s like directing such a kooky show, with a no doubt even more kooky cast.

Q: How is Soap Opera going from a director's POV?

El, director: It is going fine! We are currently in the state of taking care of production stuff. We are a bit short on time, but we are handling it! From a director’s point of view, it’s been going really well. My actors understand the directions well, there are people in the cast I can rely on, they are very involved and they seem like they are enjoying the process. It was also a little chiller than other productions, because we have rehearsals only once a week. So yeah, it’s been going well!

Q: What was the most rewarding moment in the production process?

El: Probably seeing it come together and seeing my actors understanding the point of the play and finding some things I didn’t notice. We had a discussion where we sat down and looked through the script, and we talked about what the actors found funny, what their favorite moment of the script was, how they understood their characters and hypotheticals of how the characters would behave in different settings. It was really nice to see that they get the play in the same way I do, and sometimes even find new moments that I didn’t see before!

Q: What is your overall rehearsal process like from first read-through to now?

El: It started with reading the script and doing a couple exercises. Then, we were running the script scene by scene, mostly based on the combination of actors. For example, we ran some scenes with one set of characters, but not with the other. As the process kept going, we brought them together, and now we’re just basically doing the overall runs of the script. We went off-script after the Christmas break, so now we have a finished product!

Q: To address the appliance in the room... How are you dealing with the washing machine from a production POV?

El: The washing machine is currently being made by Pavani in WDKA! We were planning to make it out of wood, but then things happened, and we can’t do that anymore. So now we are making it out of cardboard! It will be painted over, and might be a little unstable, but we are really hopeful that it’s going to work out. The issue is that there is supposed to be someone inside the washing machine, so that is a little more difficult… but we are gonna deal with it!

Q: What do you hope the audience takes away from experiencing Soap Opera?

El: Soap Opera is a very funny play, so my main expectation is for the audience to laugh a lot! There are a lot of jokes and different tools in the script: some wordplay, some references, some very blunt acting choices - so I really hope that they will laugh at not just the script, but also at the way we act it out. At the same time, I hope it brings out some sweet experiences, because the main point of the play is to not chase perfection, but notice the beauty in the mundane. I hope this gets through to the audience!

THE ACTOR’S NIGHTMARE

The Actor's Nightmare is the final of the 3 plays you will see during performance.

Written by world-renowned playwright Cristopher Durang, The Actor’s Nightmare is a bizarre and surreal comedy about the struggles of acting. The unhinged triplet of the set, it’s delivering on the worst fears of a theatre kid (failing on stage) and of a normal functioning member of society (being on stage in the first place).

We sat down with the powerhouse duo that stepped in at the last minute to steer the wheel. Lucas & Sinem, a dynamic director pair, share a little bit of what makes The Actor’s Nightmare so nightmarish.

Q: What emotions and themes can we expect from The Actor's Nightmare?

Lucas, co-director: The Actor's Nightmare is a comedy first and foremost, of course. It is very, very funny, it is humorous, but it is also very surreal. It is a very strange play, at times even a little unsettling, especially towards the end, but it is a comedy first!

Sinem, co-director: The Actor's Nightmare reminds us, in a fun and familiar way, of the mixed feelings of surprise and fear that come with being in an unfamiliar place - a feeling almost everyone has experienced at least once.

Q: Give us a quick idea of your rehearsal planning & process. How did it start, and how's it going?

Lucas: The rehearsal process is a little bit messy, just because I came onto the project very late. As you may know, they lost a director midway through and didn’t really have a lot of stuff done yet, so I stepped in as a sort of emergency because those problems needed to be solved very quickly. Right now it’s going a lot better than I first expected, but I do also feel a little more rushed than the other directors of the plays!

Q: As an actor, how do you feel about the show and what it has to say?

Lucas: I do like how The Actor’s Nightmare manages to pick out and make fun of certain stereotypes and cliches within acting & theatre in general. I also enjoy that, at least to me, it doesn’t have a much deeper meaning than that! It is much more focused on doing this and being funny, and doesn’t have a super deep secondary meaning.

Sinem: Regarding the show time, first of all, personally, I'm excited because it's the first English-language play I've been involved in directing, and because I'm working with such a young and dedicated team. As for the team, despite their busy schedules, everyone is doing their best to make the show a success.

Q: What are your actors like? How is the cast approaching their roles?

Lucas: The actors are doing a very good job! They are responding to feedback very well, and especially for how quickly we had to get into this, I think they are doing very well! It is a very difficult play to act in, just because of how surreal it is at times, especially for the main character, George. It is a very special type of role that you definitely need a lot of talent for, and not something easy to play!

Sinem: Although the actors sometimes feel tired and low on energy due to their busy schedules, I think they do their best to focus on their roles, and they are very supportive of us even in the costume and creative processes, eagerly asking questions and adding their own creativity to approach their roles. The lines sometimes scare them because they have other active roles, but I think they will overcome that :)

Q: Are you ready for showtime? :)

Lucas: We aren’t ready for showtime just yet*. There are still some things that production has to get us, there are still a couple of lines to fully memorize and some bits and pieces to make right. But on our current timeline, I’m pretty confident that we will be very ready once the date rolls around, and we are very excited for it!

*Ed. note: this interview was taken on 16.02.2026 - the cast is definitely adding the finishing touches by now!

Sinem: Ahhh, you can never really feel completely ready for the show :) And that's perhaps the most magical and exciting part of it ;) I can only say that we'll be close to feeling ready when a few small details fall into place :) We'll all see together on the night of the show. But before each performance, we really won't feel ready until it's over :)

The clock is ticking, and the seating capacity is dwindling fast! So don’t delay and purchase your ticket now:

https://studiumgenerale.stager.co/shop/wilde

And we will see you soon, beautiful and human life stories in tow, in Erasmus Pavilion!

Written by Anna Galtsova, a dedicated Writing Committee member!

You can find Anna on Instagram: @gal.tsova

Let's Review: Monologues

Two households, both alike in dignity, in fair Verona, where we lay our scene. These are the first words of possibly the most well-known piece of theatre in history: Romeo & Juliet. The narrator, who only appears twice in the play, takes a moment to set the stage, uninterrupted and without anything else to distract the audience from what they’re saying. In other words, the narrator performs a monologue. Monologues are a staple of theatre and, although to a lesser extent, film. A staple we love to quote and one we often use as a key source of characterization study when reviewing pre-established scripts. It’s an invaluable resource when writing for stage or screen and possibly one of the most entry-friendly ways into writing dramatically.

Today, we'll take a look at the Monologue: what they are and what they do, how we can go about writing one, and finally, why and when they work. Thank you for reading, now Let's Review.

I. You’ve Got Me Monologuing – Or a non-official typology

Although not completely one to one, monologues can be categorized in a few key types:

1. As a form of narration, which we will call Expositionary Monologues. These are often delivered directly to the audience and help establish the world or setting in which the piece will operate. Some examples include the opening narration of Romeo & Juliet, as well as narration by Galadriel opening the first Lord of the Rings movie. A common trope for Expositionary Monologues is prophecy, which allows a writer to quickly get a reader up to date not just on what is happening, but also what will happen over the course of the story.

2. As a form of philosophizing or self-reflecting, which we will call Verbalizing Monologues. These are delivered by a character to themselves and often reflect the inner thoughts of the character, helping to relate to their point of view or actions without having to dramatize it into a multi-actor scene. This type of monologuing is most often found in works written for stage. The equivalent tool in film comes out in camera-work, showing a level of detailed facial expressions that are hard to capture when working with a physical stage. Examples of Verbalizing Monologues are found in Hamlet’s “To be, or not to be” monologue, helping understand the mental anguish he is in and his struggles between action and inaction, and McBeth’s “Is this a dagger” monologue, showing the start of his paranoia and regret over his betrayal.

3. As a form of positioning the character in relation to others, which we will call a Statement Monologue. While the first two types are most often delivered with a character alone, the Statement Monologue is almost exclusively performed by a character in relation to others. The most widely known trope is that of a ‘villain monologue’, where the antagonist of a story proudly explains their plans and how they despise the protagonist of the story, helping to create clear relationships between different characters. Dramatic examples include Shylock’s “If you prick me, do I not bleed” monologue from the Merchant of Venice, where Shylock decreases the distance between the antisemitic citizens of Venice and its Jewish population, or the “You can’t handle the truth” speech delivered in the movie A Few Good Men, clearly setting up the differences between Daniel and Colonel Jessup.

4. As a form of persuading or motivating others, which we will call a Rallying Monologue. Where most of the other subtypes may not often be used in film, the Rallying monologue is the exception. Usually performed by the main protagonist, we see examples in movies like Independence Day, many fantasy and science-fiction movies like Lord of the Rings and Dune and in television series like the West Wing. The key element of the Rallying Monologue as opposed to a Statement Monologue is that while a Statement monologue serves to outline who characters are in relation to one another, the Rallying Monologue goes further to try and change the belief or action of another character to that of the protagonist.

5. As a form of direct audience address, which we will call a Directed Monologue. The literary term for this is an ‘Apostrophe’ and is distinct from narration because the characters remain within the story, as opposed to looking at it and narrating it from the outside. Fleabag makes extensive use of this by acknowledging the fact that the story is being told to the audience as a participant in the story, which is its key differentiator from the Verbalizing Monologue. Another example of this is the explainer-type Directed monologue, usually found at the end of detective stories or whodunits and delivered by the main character, helping the audience to understand and ‘solve’ the mystery.

From these broad subtypes, a few key questions seem to emerge:

- Who is the character speaking to?

- What is the purpose of the monologue?

- Is what is being said objectively true (Narration, Verbalizing) or subjective (Statement, Directed, Rallying)?

- Is the character aware of who they’re monologuing to?

With these in mind, we can begin to design our own Monologue.

II. Or not to be, that is the question – Or the mechanics of writing a monologue

There are a few things we need to engage with a monologue. First, monologues depend on the context of the play (and the context in which they were written) to resonate. Second, a monologue has to deliver some kind of message. Third, monologues are directed to a certain audience and finally, they are delivered by a character. Together, we can refer to these elements as CMAC and depend on them as we begin to build our monologue.

Context is the most broad and usually determined by the script you choose or write. We can define context as ‘the entire set of facts and circumstances around the action happening on stage/screen’. This can be as expansive as early 19th century France (Les Miserables), Middle Earth in the Third Age (Lord of the Rings) or 1940s Europe (Saving Private Ryan) or as small as a living room over the course of a day (Carnage) or a piece of garden (A Bug’s Life). A quick structure to get to context is by naming a place and a time. After deciding on a context, we can populate it by adding detail. What defines your context? What important elements belong to it? What kind of struggles were happening at the time? What kind of victories? Where are we? What cultural elements will impact or shape our context?

If you want to write a monologue yourself, quickly sketch out 3-5 Contexts. For each of the contexts, answer the following questions:

1. What cultural elements or factors are present? Which one(s) is/are dominant?

2. What does life look like for someone within your context?

3. How is your life different from the lives of people within your context?

After establishing a context, we have to determine the Message. The message is a clear statement that describes what the monologue is about. It can be as simple as “The monologue describes someone’s day” or “The monologue is about dealing with grief.” This will become your guiding line throughout writing the monologue. Whenever you ask yourself what comes next, you refer back to the message statement and connect whatever you are writing to that. A general rule of thumb is that a monologue can have multiple messages, but never more than one at the same time. A monologue like Romeo’s goes from “I am in love with her” to “We can’t be together” to “I have to find a way”. This guides the audience through a line of thinking that a singular “I love her” would not have captured. For directors, this is referred to as the ‘through line of action’ (Stanislavski, Meisner).

For your monologue, determine whether there is one or multiple messages. Write each of them down in a one-sentence statement on different pieces of paper. Which order should the messages take? Determine the order and label them with a number.

Audience seems simple at first but determines a lot regarding how a monologue is structured. The audience at the start of a play may only know a surface-level amount about the story or may not know anything at all. Characters within the story should know the context of the play (or at least those they would realistically have access to. From our earlier typology, we can broadly say a monologue can be directed at Self, a different Character (or characters) or the Watching Audience. When making this determination, think about what your audience knows at the beginning of the monologue and what they should know by the end. Also keep in mind that although the Watching Audience may not be the targeted audience of the monologue, they will be the ones experiencing it in the end. Hiding information from the Watching Audience will create a risk that they may miss it. That is okay. Make sure that this is a conscious decision when writing the monologue and be aware of the risk.

For your monologue, determine your audience. Write down what they know before and after the monologue and how this changes how they feel or think about the character. For each message, write down 2-5 key points you want to bring across to the viewing audience. What risks do you see? What opportunities arise from this specific choice of audience?

Finally, we get to Character. By this point, you will have an idea of the context of your monologue, what you want to say and who you want to say it to. Character determines how you deliver the monologue. Characters, on the most abstract level, are a walking ‘mini-context’ of thoughts and ideas, both about themselves and the world around them. By determining how your character works, you will understand how your monologue should be delivered. This includes the conscious (how does the character think) and unconscious (how does the character feel) parts, as well as the visible (what language do they use, how do they talk).

For your monologue, we start by sketching out a character:

1. In a few lines, describe the character’s context (how does it differ from the context we established at the start?) What does it mean to be this character in this context?

2. In a few words, describe how the character talks (short, eloquent, clipped, upbeat, cheerful, dour, angry, mischievous, lisping, stuttering, verbose, dry).

3. For each of your messages, determine the following:

a. Does your character know what the message means?

b. How does your character want other people to look at them?

c. How does your character think of/look at themselves?

d. What does your character think of the Audience?

4. For all of the above, determine with each Message and Key-point how this interacts with your character. Does it scare them? Are they happy about it? Do they want to hide it? Do they want to be proud of it?

If you followed along with the practical exercises, what you have now is a clearly defined context, a planned outline of messages and key points in a chronological order, a clearly defined recipient / audience of the monologue and an outline of the character that is supposed to perform it. All that is left to do is to write the monologue itself.

III. Everyone can cook – Or what makes your monologues work

Armed with the above outline and with a clear idea where our monologue fits in the typology, we can begin writing it. Ultimately, what makes the text of a monologue work and stick with the audience is highly subjective and differs from writer to writer. However, there are some key guiderails to help you make your monologue flow.

- A monologue is personal. Whether delivered full of facts or incoherently and straight from the heart, it will forever change how we view the character. It reveals what might be hidden or it clearly shows that the character is hiding something. The point is not to solely deliver a speech or debate. These can be done in many other places outside of film and theatre. Where our craft differs is the fact that we add a layer of emotionality to what is said.

- A monologue is spoken. A great practice for writing monologues is to speak it out loud as you finish (parts of) it. You will immediately hear where lines need to be adjusted and what does or does not sound good to you.

- A monologue is heard. Going together with the former, it helps to deliver your monologue to someone you know to see whether they understand what it is you’re trying to say and how you’re trying to say it. If follow along and engage, chances are your audience can too.

- A monologue is fleeting. Unlike written works or recorded speeches, dramatic monologues exist only for so long as they take to be performed. This means that whatever messages you want to share, it should be possible to follow them even if the audience cannot review what is being said. Limit the amounts of simile and metaphor to one or two striking elements and add extra emphasis on the personal elements, which will stick much longer than recollection of the actual text.

- Finally, a monologue is rehearsed/planned. This is important. Sitting down and writing a monologue means thinking about and feeling out everything we have reviewed so far. It is different from the impromptu speech or improv theater because we intentionally create our narrative and give ourselves time to prepare it. Relying solely on improvisation and a very rough sketch can yield tremendous results, but will ultimately not allow you to repeat it reliably.

Before we finish: There are books on writing that strongly encourage you to simplify your messages to something everyone can understand. This does not mean that you should dumb down your message or intended idea because your audience won’t understand. Film and Theatre as a medium are sometimes not meant to be understood or even enjoyed by everyone. This is especially true for monologues that exist as individual pieces. By treating our audience with respect and viewing them as complex individuals with their own perceptions and ideas, we encourage them to interact and engage with our writing. This is the core of dramatic craft and ultimately what differentiates passable writing from truly unique and exciting monologues.

IV. So this is Monologues? – Or the thing in review.

Today, we have reviewed monologues: what they are, how they are structured and what makes them work. If you followed along with our exercises, you made a clear outline and, based on our writing takeaways, have possibly even finished a full monologue! You now have a working, basic understanding of what it takes to write one and in doing so, have thought about how to perform it or direct someone else performing it. If you’re not quite ready yet, keep going and finish the project. It need not be long, even a page is enough to say you’ve written a monologue.

Read it, show it to someone and/or start the next one.

If we approach theatre as a craft that takes some time and practice to get used to, you’ll see that you begin to improve very quickly. Repeat the exercises and write a few short or mid-length monologues before going into a long one. Read publicly available monologue collections and apply our review to them to be able to take what makes them work and add the tricks to your toolbox.

If you are excited to share your work, please send it to wilde.eur@gmail.com. If you want, we can provide feedback or help you overcome a challenge.

Until then and see you next time where we add an extra dimension for Let’s Review: Dialogue

Written by Thomas van Eijl, a dedicated member of the Writing Committee and a veteran of WILDe

You can find Thomas on Instagram: @thomas_the_dutchman

3 things that make a screenwriter - and 3 things that break one

Will you become a screenwriter?

At the end of the day, that’s the honest question.

First off, let’s get the deets out of the way: you will probably never become a famous screenwriter, and you will probably struggle to sell a seven-figure script. That’s just statistics - no hard feelings.

That’s not what this question is about.

Will you become a screenwriter: will you trade your soul for sitting in front of Final Draft, writing 2 words an hour, then slamming your laptop, then getting a coffee, then pacing around the room for that perfect twist, then lurching back to your work in a frantic attempt to write down your next brilliant idea - and more importantly, will you be able to do this for days, for months, for years, for hundreds of scripts?

I must preface this list by saying I’m still not sure which side of the fence I fall on. I’ve definitely written a lot of scripts, and that mass definitely had its flaws. I sat in front of my own plan today, and I could not write a word - not even the 2 words an hour I so haughtily wrote about earlier. It made me afraid, and it made me curious.

What makes someone write - and what makes one stop writing?

I hope to answer that question for myself and anyone that is wondering. So, in the best Buzzfeed tradition, let’s think through 3 things that make a scriptwriter - and 3 things that break one - together.

Make 1: watching movies

I know, I know. To be a screenwriter, you have to watch movies. Shocker.

Still, you’d be surprised how many people that want to be screenwriters don’t actually watch a lot of films. I say this somewhat vulnerably as someone who regularly stops watching for months - and has to make a conscious effort to pull myself out and watch something for Pete’s sake. (Shoutout to my sister, an insane movie nerd, who drags me into movie theaters and puts on films I want to watch. Her mind terrifies me and I could never be her. Thanks Nastya.)

There is another group: people that restrict themselves completely arbitrarily. “I won’t watch it if it was made after 1990”, “I won’t watch it if it’s black and white”, “I won’t watch it if it’s under 60% on Rotten Tomatoes”.

You need to consume fast food to be a chef. You need to know Picasso to be a painter. Sometimes, you need to see animal guts daily if you want to be a vet.

Sometimes, you just aren’t a movie aficionado. That’s okay too. After all, there are a scary number of movie classics I haven’t watched, and I will one day catch up with that list.

But if film, by choice or by need, is something you must get into, you need to watch film.

How do I get there?

Start with the classics. Don’t fall into my trap and watch the oldies that everyone talks about. If you don’t see why they’re iconic, at least you form your own opinion;

Fall in love with its versatility. Citizen Kane, The Room and Avatar are all movies. Good or bad, funny or scary, pretty or real - they’re all films. Isn’t that cool?

Don’t be ashamed to be kind to yourself. Maybe, as you watch on, you will discover that this is not for you. And that’s okay!

Break 1: not seeing your movie and story

Not in some beautiful poetic sense. Can you actually see what you’re writing about? That’s often the deciding call.

For the longest time, I was convinced I had aphantasia. After all, the apple test landed me between a 4 and a 5 on a good day, and I still cannot picture anything actually moving in my mind’s eye. With training (Reddit helps *shudder*), I was able to inch that to a 3-4 rating, and I’m glad I did.

This doesn’t matter too much when you write fiction books, but screenplays are strictly visual. There’s no way around it. (Sorry, first person POVs, you’ll stay confined to novels.)

Simply put, if you can’t see it and you can’t hear it - it has no room in a script and will only serve to waste the real estate of your work. You have 120 minutes max to make your point, and while you might cherish what your characters are thinking or feeling, if your client, director or industry worker can’t put it on a screen, it’s a lost cause.

As you can imagine, not knowing exactly how each moment looks in a scene, how the audience sees the woes of your characters, and what the audience is perceiving, not just seeing, hurts your point pretty badly.

How do I fix this?

Write a whole script without any dialogue. Words are a crutch for your inner voice - so tell it to shut up and pass the mic to your mind’s eye.

Watch movies intentionally. Observe, take visual notes, shamelessly steal tricks from the gurus. Ask yourself - why did this old white man point the camera that way?

Daydream. Put your laptop down and let your 15-year-old self dream. My hot take: this is a valid and necessary part of writing, especially of a script.

Make 2: falling deeply in love with your story

A “good" story is subjective. You may doubt your screenplay is any good, but for someone else, it can be their saving grace that pulls them out of misery. I loved Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (before JKR became who she is now, just saying); to others, it was a bunch of nonsense, and they made sure to tell me about it.

Often, the key to being a good (screen)writer is simply that - being able to love your script, your story and your characters.

This ‘make’ is the bread and butter of how we writers live.

Your passion relies on being deeply infatuated with every crevice of your screenplay, understanding exactly what place in your heart your story occupies, and why it draws you to wake up, pick up a laptop and keep on writing. That passion is contagious - and is often the immediate hook to make what you do truly a good work.

If your heart is not on fire for the story that you’re trying to tell, if you don’t want to shout your key message from the rooftops, if you aren’t just slightly crazy about your blorbos and your plot beats - then sorry to say, your well will be dry very soon.

We writers are fundamentally lovers. In a very messed up way, we love our own minds.

How do I get there?

Indulge yourself. Pick a storyline that has happened to you, a character that represents a dear friend, or a lore detail that represents something only you know.

Praise yourself very casually. The little thumbs-ups you give yourself along the way boost your confidence by a lot. Wrote a nice page or two? Tell yourself ‘good job’!

Don’t hesitate to kill your darlings. It’s different if screenwriting is your income, but if you have the luxury of writing for yourself, don’t start if you don’t believe in an idea.

Break 2: being too smart

To all the people who think they are extremely smart and cool and sexy and fabulous - chapeau, but you, too, can suck sometimes, actually.

The average audience member is tired and doesn’t want to think. That’s not cynical commentary on the state of the world, that’s the reality of the bodies we live in. Most people don’t actually want to think even more when their brain is already being too loud. That’s how we got TikTok to take off.

Your story must be simple, and that is an essential need.

Now, what about the arthouse and the indie and the conceptual? Yes, it still pays to be simple, sharp and direct about the premise, or people will yawn themselves out of the theatre. (And notice how so many people do avoid the above for this very reason.)

In Save the Cat, Blake Snyder posits that if you can’t summarize your idea in 1 sentence, studios won’t give it the time of day. Blake Snyder’s concern with money above all is a thought for another day, but in this instance, I agree: your story must resonate with everyone, be full of raw, understandable feelings, and deliver on them in a punchy way.

Often, the smartasses of the world don’t have the heart to do this.

How do I fix this?

Run a simple checklist. Is your idea clearly understood by everyone? Do you know why they feel that way? Do you see them staying for the whole 90-120 minutes?

Summarize the movies that became icons in 10 words max. Ordinary farmboy rebels and stomps a dictator. Yep, I can see why millennial teenagers loved Star Wars;

Feel your own feelings, deeply. You’d be surprised how much more profound and relatable your stories get once you stop intellectualizing and cry for yourself.

Make 3: locking in

Screenwriting is a lot less fun than people think. A lot of your time is spent forcing yourself to write just a little bit. Yes, without a podcast to muddle your brain with words. Yes, without a YouTube short to rot your brain further. Yes, without a girl treat to keep you going (okay, maybe that one’s alright sometimes).

At the end of the day, all you can do is write - and that’s actually pretty frustrating.

Sometimes, you will fail to even open that damn project file. Sometimes, the world will seem like it’s out to get you and your creation. Sometimes, your dopamine rush wears off and you just don’t see the point anymore.

And yet, you must keep writing.

Your idea is probably awesome, but nobody is going to read it until it’s done, and chasing the next sparkling butterfly is what kills your work the fastest. Screenwriting is often seen as this passionate, driven, inspired hobby. Most of the time, it’s plain boring discipline.

Being comfortable with being lazy, stupid or depressed - and writing anyway. That’s often what makes or breaks a script.

If this process isn’t done, who’s going to care about your great concept of an idea?

How do I get there?

Remember your key message. If you don’t burn to tell the world something, you’ll run out of gas. What made you write this in the first place? Hold on to that;

Use a calendar! Scripts, fundamentally, are a boring numbers game. X pages by Y date - that’s the formula, and it’s much more trusty than chasing a vibe;

Rest, a lot, and don’t be a dick to yourself about it, but write at least something every single damn day. Sometimes, all it will be is 1 line, and that’s ok.

Break 3: going by the vibes

You are in love and you know how to write - great! Perhaps you can even attract your audience’s attention, impart some knowledge upon them, or inspire them.

Turns out, once your big writer pants are on, you might discover you don’t know how to write.

For my part, I was convinced for quite some time that I understood how storytelling works. After all, I could finish a story, and people liked it. When I started writing for others, though, I quickly realized there is much more for me to learn than what I could do without deep study. What do you tell the person you’re writing for when they come back with “the pace just feels kind of off”? When they “just hate how this guy sounds”? When “idk, I don’t really feel the narrative” is your only feedback piece?

You try to learn. A lot.

There are a lot of ways to do so. Story structures (Hero’s Journey, Save the Cat, the story circle, etc.), numerous books on (screen)writing (Syd Field’s ”Screenplay”, Joseph Campbell’s “The Hero with A Thousand Faces”, Stephen King’s “On Writing”), countless podcasts (not really a podcast kind of gal, but someone out there must be) - a lot of variety exists for you, and it’s a mandatory step to writing quality and knowing how you did it.

How do I fix it?

Research what you would like to do, then dive deeply into that genre, that trope, that audience. Research what the best in the field use, then pick up that theory;

Consume a lot of media. Movies are a must, we already established that, but even reading, playing video games or listening to music exposes you to stories;

Be humble. You’re not too good to study. You’re not too advanced for the basics. You aren’t a prodigy that can succeed without understanding how you did all that.

Well, that’s the list.

If anyone ever finishes this all the way through, I’m in your corner. Every writer worth their chops must go through a crisis sometimes, and if that’s where you are at, consider this a badge of honor and a ‘you made it’ moment.

Will we become screenwriters? Dude, I don’t know. But I’m here for the ride, and until my engine dies, I will continue the drive.

Now, if you’ve made it this far, can you maybe message me? I’m stuck writing a scene about washing blood from white hair.

Written by Anna Galtsova, a dedicated Writing Committee member!

You can find Anna on Instagram: @gal.tsova

Speak it like Beckett

December 17th.

Today I have lost the ability to speak to people. I opened my mouth but I could not find the words. Nothing was adequate.

My father made me an omelette. I could not thank him. Our eyes passed each other by and waved while my mouth kept twitching. At one point I opened wide, teeth out, silent. Dad laughed and brought me another chunk of the yellow-black, overdone slop. I could not eat it but finished it anyway. “Hhmphg,” I grunted. Dad turned to me and asked: “It was that good, huh?” Another grunt. Nothing was adequate.

I went up to the tree that grew through the middle of the living room. Maybe, at least, I could get myself to say something here, address it to the branches. Somebody had left a massive softcover copy of Samuel Beckett’s Collected works floored blunt on the roots. I saw it and I finally, for the first time that long morning, knew what to say. “Samuel Beckett’s collected works,” I told the tree. The tree said nothing. Maybe it was just that sort of day, and my family’s deranged living symbol had also lost its ability to speak. Who else?

I picked up the book. It was surprisingly light. Light meant smart and quick and easy. This Beckett would teach me how to speak again.

I went back to face my father. My vocal chords redirected all the formed sounds back into my lungs. U-turn cop-out. Nothing was adequate.

My middle part of the day was spent on the park bench peering at the Beckett pages through a polka-dot scarf.

December 18th.

It’s been a week or maybe a month and a week since I have lost my ability to speak. Beckett’s helping.

In the morning, the woman at the grocery store, with her usual look of profound pity, asked me if I wanted a plastic bag. I thought of the usual pictures of dead leather-shelled turtles. “It was a little child that fell out of the carriage, Ma’am,” I told her. “Oh god, oh god oh god, what happened?” She said, pitying me or maybe the little girl. I left the store carrying the milk, carrots and bananas I had bought cradled precariously in my hands.

The middle part of my day was spent on the park bench helping the wind flip the pages of Beckett’s collected works.

December 19th.

Yesterday I lost my ability to speak.

Beckett teaches that one does not have to speak. I can be A, or perhaps B, from the Act Without Words II.

My father made me an omelette today. It was burnt and smelled of pinched needles. I sat down on the chair and demonstratively crossed my legs. In my shirt pocket I found a carrot and a banana. I put the banana back in my pocket and chewed on the carrot. It tasted like metal. It had soaked in the stench of the room. The message I wanted to communicate to my Dad was this: it is alright, I do not need the omelette, you can sit down and relax and not work so hard. My father frowned and pushed the omelette towards me. I kept chewing the carrot. Snap and crunch.

“Yes I know, it’s a little burnt, but you have to eat… you haven’t been yourself,” Dad crooned.

After a while, he reluctantly shuffled the plate back away from me. His eyes searched mine. His mouth opened to speak, but stopped short. His hands threw the plate vigorously onto the floor, where it smashed against the roots. The tree would be happy; the tree would feed, burnt or not.

Beckett’s words twirled and pranced around in my skull.

Nothing was adequate. Tomorrow I would have known what to say.

I spent the middle of the day periodically wiping fallen leaves and dust off Beckett’s collected words.

December 20th.

I woke up some time ago and found I could not speak. This did not last very long. After months of studying Beckett I am able to speak like him without quoting him directly. The key is to imagine the person I am talking to is not really there, and the words I am saying are addressed to Beckett, while He is testing me on the adequacy of my interpretation of his collected works.

Several times people have gotten up in a fury over my conversation.

“Nobody talks like that,” they say, lips taut. But I know somebody talks like that. And I know, as well (and this is something He teaches) that words and patterns create universes, and sooner or later the power of my unique form will convince my co-conversationalists that there is a world beyond “everybody”, a specific place where how I speak is the law of things. Speech and motion and their repetition are what makes life, and saying that my speech does not correspond to reality is to simply be outdated. As I speak, I update what is possible and what is real. In this I follow Beckett and his collected works. His characters never spoke “realistically”, instead they birthed patterns of words, and words make logic and logic builds an understanding of the world.

I spent the middle part of my day peeling bananas and throwing the peels down to feed the park grass. I did some reading too.

December 21st

Beckett teaches that my father is not my father, but a father. He is also a signifier, or a variable. A,B,C, maybe D or X or 23 or Dad. He is a signifier who has attributes and lines. One of those attributes is that today he has made me an omelette. Another is that he, along with Beckett, will die tomorrow. 22nd of December, Beckett’s death day. I don’t feel much connection to him. Or my father for that matter. Like his characters, I now feel like I have nothing to do with anyone else. I am adequate for nobody.

The worlds I have spoken into existence have all disappeared the very next second. I am increasingly certain, however, that most ideas are best explained by well placed picture words. A couple words that do not try to explain but let you feel the presence of the things described, invoked; this is how you plant the seeds of ideas. Beckett may have had something to do with that thought.

The middle part of my day was spent wondering where the later parts of my days go.

22.12.

Here I note, in some attempt to calm my scurrying thoughts, the case of the matter. I found this diary just now, the evening of the 22nd of December, in my room, on my bedside table. It does not belong to me.

My own father has been dead for 7 years. I have not read a page of Samuel Beckett in my life. Maybe I have seen Waiting for Godot staged in a park some summer, but I’m not sure -- that may have been me imagining someone’s retelling of that event. Whatever. What disturbs me more is this, on my table. Whoever wrote this is definitely not me, so how did it get here? We bear one similarity, me and this time-addled author. We both have a tree growing through the middle of our living room. The parallels end there. I will ask around, then try to forget. But right now, there is such silence. I feel like my breath has been vacuumed out of me. I am starting to think the earth might be uninhabited.

Written by Yan Nesterenko, a dedicated Writing Committee member!

You can find Yan on Instagram: @n_strenkyn

A Sinful Cast Interview: WILDe's Next Murder Mystery

Written by Anna Galtsova, a dedicated Writing Committee member!

You can find Anna on Instagram: @gal.tsova

Performance v.18

FINAL_FINAL_LAST_VERSION_Performance_v.18.docx

"Performance"

INT. SOUNDSTAGE - EMPTY SET

Curtains open.

White lights fade in, revealing a bare stage. The back and side curtains are pulled up, letting the audience see into the wings. Ropes swing by the side of the set. A ladder creaks. There is nobody there, but the full technical equipment of the theatre is exposed, vulnerable.

Backstage, there is a low rumble. Conversations echo through the wall and increase in volume quickly with manic energy. The tension builds. Someone yells. Something clangs against the floor. A switch flicks on and off and on again. A distant piano plays a song off-tune. Noise, noise, noise,

And suddenly, silence.

The first backstage door swings open.

THE SKILL walks in through stage right with a solemn look. He wears a feathered hat and historic clothing. He walks center stage, downstage.

There is a moment of quiet as he stares into the audience, before he closes his eyes and takes a deep breath.

THE SKILL

(Dramatically.) All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages–

A laugh is heard from stage-right, and THE SKILL flinches.

THE PASSION walks in through the second backstage door with a confident smile. He wears a glamorous modern suit, sparkling in the stage lights.

THE SKILL turns towards him, annoyed.

THE SKILL

What? What is it?

THE PASSION walks forward, standing stage-right. THE SKILL steps back.

THE PASSION

Nothing, nothing. (Beat.) I just… find it silly. Don’t you think that monologue is a little outdated?

THE SKILL

It's Shakespeare.

THE PASSION

Exactly. Why are you doing that dumb posh voice?

SKILL

(Offended.) I'm not doing a voice. This is the character. I'm playing a role.

THE PASSION

Isn’t ‘As You Like It’ a comedy? You sound waaay too serious.

THE SKILL rolls his eyes and crosses his arms.

THE SKILL

The character, Jaques, is supposed to be cynical. He is a philosopher. His overindulgence in melancholy is intentional. He stands apart from the world in order to understand it.

THE PASSION

That doesn’t sound very comedic, I’ll be honest.

THE SKILL turns to fully face him.

THE SKILL

(Frustrated.) Then go complain to Shakespeare’s grave. ‘As You Like It’ is a traditional classic. It’s great. You just have poor taste.

THE PASSION

My taste is great, it’s just a lot more modern. So, you know, it actually applies to my life. I don’t really care for stories that aren’t relatable.

THE SKILLS

Old stories are just as relatable! The themes and ideas are still there, even if the words themselves can be somewhat out of style. I’m just honoring the text.

THE PASSION

No, you’re obeying it. There’s no honor in that.

THE SKILL stiffens.

THE SKILL

Excuse me?

THE PASSION

You heard me. You’re obeying, not honoring.

THE SKILL

This delivery is just… It’s just how it’s always been performed, okay? All actors before me have echoed the author’s voice, to convey the correct message. It’s just how it always is. I won’t change it.

THE SKILL adjusts his clothes with a stubborn arrogance. He steps forward elegantly to return to his monologue, but THE PASSION quickly pulls him back. They split the stage half-and-half.

THE PASSION

Yes, sure, but enough time has passed. Things change. You’re preserving the text, not the thought behind it.

THE SKILL

The thought is the text, that’s the point. You can’t honor a performance without understanding what it was originally meant to achieve, and the writers’ intentions can only shine through in their words. Meaning doesn’t exist without form.

THE PASSION

I disagree. For starters, most of Willie’s old plays were for the commonfolk, not the wealthy. He'd be rolling in his grave if he heard how pretentious you're sounding.

THE SKILL puts his foot down, pushing THE PASSION a bit farther away.

THE SKILL

Will you stop critiquing my accent? I know what I'm doing.

THE PASSION

Do you? Sounds to me like you're just copying better actors.

THE SKILL pauses, visibly upset at the comment.

A beat.

For a moment, it looks like THE PASSION’s face reveals a glint of regret; a sudden sadness he isn’t voicing.

Just as THE PASSION goes to step forward — perhaps to apologize — THE SKILL takes a step upstage in a dramatic faux reverence.

THE SKILL

(Sarcastically.) Well, then, oh, great director. Show us how to do it right. Please, enlighten us with your amazing ability.

THE PASSION pauses for a brief moment, before he walks forward defiantly, a dance-like flow to his step. He looks off to the side with a flame in his eyes, gesticulating vaguely in the air as he talks. He glances right at the audience, even directly locking eyes with some front-row audience members. He has an ambitious charm.

THE PASSION

Life is like a play with no script,

and everyone follows along in their roles.

We come into the world, and eventually leave it;

but in between, we force ourselves to put on masks.

We pretend to know where to go, what to do,

but we all play seven roles–

THE SKILL rushes forward, dropping his face in his hands.

THE SKILL

Stop, stop.

THE PASSION

What now?

THE SKILL

You got it all wrong. That isn’t the monologue. At all.

THE PASSION

Yes, it is.

THE SKILL

No, you’re just babbling some vague ideas.

THE PASSION steps forward, looking ahead as he delivers his monologue. He gets lost in his thoughts as he speaks.

THE PASSION

But that's what it feels like, isn't it? We all live our lives in a performance. The world is a stage, while everyone else is watching and judging. People are born, they grow, they fear, they change, they fail, they learn, and then they die at the end. The idea is the same, right?

THE SKILL paces behind him, disappointed.

THE SKILL

You’re doing a disservice to the original text. There’s so much value, so much history, in the original choice of words. You can’t just improv your way through them because you feel like it.

THE PASSION turns back around.

THE PASSION

(Resolutely.) Yes, I can. It’s how the text makes me feel, so that’s how I’ll say it.

THE SKILL

If everyone bends the text into whatever they believe in, it becomes arbitrary. Theatre isn’t here for you to overwrite nuance with your own worldview, just so you can, what, feel seen? Characters aren’t supposed to be your mirrors.

THE PASSION walks towards him.

THE PASSION

But how am I even supposed to perform a role I don’t see myself in? What’s the value of speaking words I can’t believe in? It’s not acting if you’re just reading the text.

THE SKILL

Actors are vessels. We carry fictional worlds, stories, morals, so much larger than ourselves. It’s not acting if you’re just being yourself. Then it’s just reality.

THE PASSION

Well, I think–

THE SKILL

No one cares what you think. This is about the story, not about you.

THE PASSION steps back at THE SKILL’s confrontation, in surprise and offense. He turns away in frustration, facing the audience for a moment before slowly walking away stage-left in anger.

THE SKILL

Theatre isn’t about your own indulgence. You have to understand the craft, the insight, the versions of stories told before… You can’t get so lost in your own delusions, in the beating in your chest, that you forget the message you’re actually trying to tell. The audience will leave empty-handed. You can have all the fantasies you want, but without effort, without structure–

THE PASSION, lost in his thoughts, stops at the stage’s edge.

THE SKILL

–You’ll overstep without knowing the way forward. You’ll just fall into the pit.

THE PASSION pauses at the edge off to the side of the stage, just before the orchestral pit. He looks down into the dark pit. He sighs, before sitting down right at the ledge and letting his legs swing.

THE PASSION

But, if actors speak what they don’t believe, the stage becomes a lie. And you know the audience can sense that, too.

He looks up at the audience as he speaks. THE SKILL moves closer.

THE PASSION

There’s no point in living so systematically, so performatively, you forget to actually live. Why do you think every theatre production is so different? People’s experiences are all unique to them.

THE PASSION turns quickly towards THE SKILL, and he freezes, embarrassed for getting caught in his interest.

THE PASSION

You can read all the books about theatre guidelines and memorize all the little key terms, but there’s no rules or laws to real emotion.

THE PASSION turns back forward, while THE SKILL mumbles to himself, tired of the discussion. He pulls out a small notepad from his pocket and begins to flick through the pages.

THE PASSION

I’d rather fall than not have spoken at all. And yeah, sure, okay. Characters aren’t mirrors, but our job is to make them feel real. They’re fragments of us, in one way or another, just as we take fragments of them into ourselves.

THE PASSION waits for a rebuttal, but THE SKILL stays quiet.

Instead, THE SKILL walks forward and sits down beside him. He takes a pen out of his pocket and clicks it.

THE PASSION looks back at him, confused.

THE PASSION

What are you doing?

THE SKILL

Tallying.

THE PASSION

(Disillusioned.) … Really?

THE SKILL

Yes. This is the… 18th time we’ve had this argument.

THE PASSION

(Scoffing.) You really never change tradition, do you? We keep going in circles, and still you never actually listen to me.

THE SKILL

I can listen to you just fine. You literally never shut up about anything.

THE PASSION

How can I be quiet? (Sighing gently.) There are so many beautiful things to feel.

THE SKILL

Too many, maybe.

THE PASSION

I won’t be silent about my excitement when given a spotlight.

THE SKILL flicks through his notepad a few more times, before putting it back in his pocket.

THE SKILL

I’m afraid I’ll never properly understand you, but I…

He hesitates, as if he couldn’t believe he was admitting this.

THE SKILL

I don’t dislike you.

THE PASSION

(Prickly.) You act like you do.

THE SKILL

(Softer.) Of course I do. A performance feels safer, doesn’t it?

THE PASSION looks up suddenly, in concern. There is a deep understanding in his eyes as they share a look. THE SKILL looks back down, flustered.

THE SKILL

But I’ve studied enough to know your importance. There’s not much point in writing a story if there’s nothing to write about. You matter just as much.

THE PASSION takes a moment to process this, looking away. He smiles to himself sweetly, before a sudden realization pops into his head.

THE PASSION

(With sass.) …I know what you’re trying to do.

THE SKILL

Do you?

THE PASSION

You’re trying to get me to admit that I still need your technical knowledge, that my excitement can’t flourish anywhere without your little structures and rulebooks.

THE SKILL grins to himself.

THE SKILL

Oh, hm, am I?

THE PASSION

Yes, you are! You’re always like this. If you’re trying to get me to confess that I need you, then I have bad news.

THE SKILL scooches closer, leaning over THE PASSION.

THE SKILL

I’m not trying to do anything; you already wear your heart on your sleeve. We both know you would be nowhere without me. I can read between the lines just fine.

THE PASSION grins madly, a sneaky tone in his voice.

THE PASSION

…Oh?

THE SKILL

What?

THE PASSION

So you say… there’s meaning between the lines? It’s almost like–

THE SKILL pulls away, embarrassed.

THE SKILL

Don’t.

THE PASSION

It’s almost like… you can tell the meaning… without the text.

THE SKILL

Stop that.

THE PASSION

It’s like the feeling matters more than the form, or something. Woaaaah, that’s crazy.

THE SKILL

(Chuckling.) Your understanding of comedy is very twisted.

THE PASSION

And still, you laugh.

The two share a small laugh, before THE SKILL gets up. He extends a hand to THE PASSION, who takes it, allowing himself to be pulled up.

THE SKILL turns to the audience, smiling fondly.

THE SKILL

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances…

He turns towards THE PASSION, and loses track of his thoughts.

THE PASSION

But we keep forgetting the script, don’t we?

THE SKILL laughs quietly to himself. He takes a deep breath.

THE SKILL

Let’s go from the top.

BLACKOUT.

(Come to the Night of Short Plays!)

Written by Ana Clara Martins, a dedicated Writing & Marketing Committee member!

You can find Ana Clara on Instagram: @anaa.logy

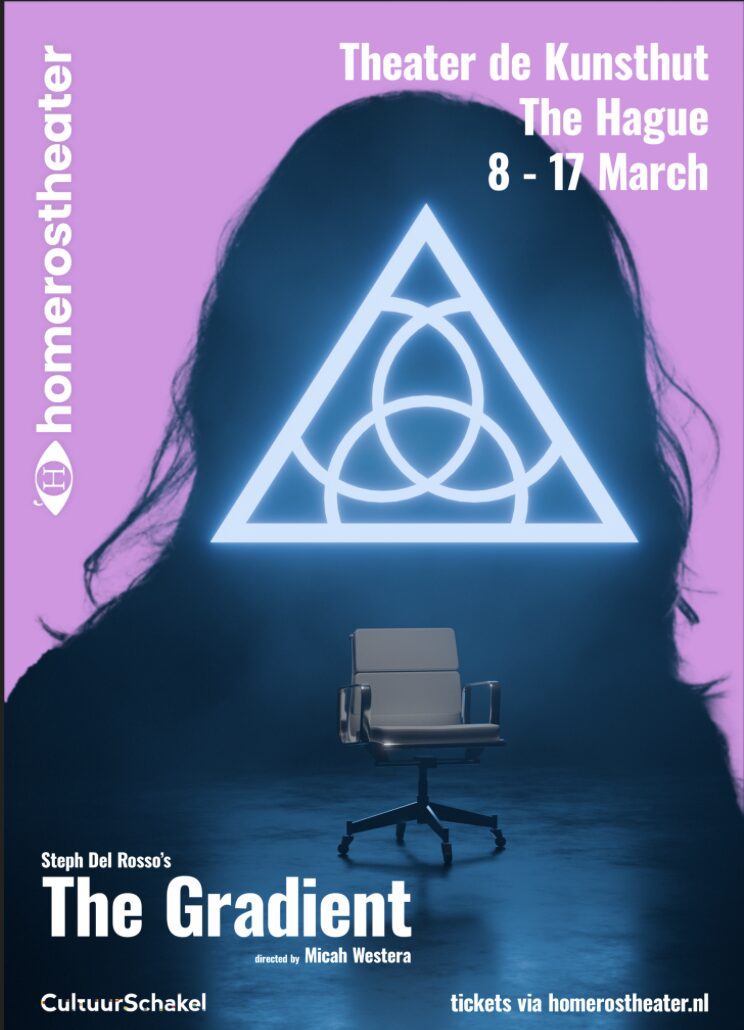

The Fifty Shades of Grey in “The Gradient”

"There is probably no genre more realistic than satire. If novel is a mirror carried along a high road, like Stendhal claimed, satire is a stone thrown at it to show you what’s hidden behind. And while it is depressing to admire your face in a shattered mirror, and it might bring you seven years of bad luck, it sometimes is just high time we stop staring at that piece of reality that is conveniently framed into what we feel comfortable examining. “The Gradient” is a stone that flies smoothly, almost deceitfully, and shatters your comfort zone slowly, piece by piece. It leaves you frustrated and uncomfortable. Wishing someone would hang that mirror back up there. Or a generic photograph that comes together with an IKEA frame. And it does all that in such a satisfying manner that you almost fail to notice.

Realism Behind VR Glasses

The feeling of frustration is not caused by the plot itself (however unbearable some characters are), as much as by the disappointing realisation that we’ve just witnessed the reality in which we find ourselves on a daily basis. The way the play was constructed enhanced this impression. It sometimes felt like we were spectating a regular conversation in an office, especially whenever Tess and Louis appeared on the scene together. Witnessing the development of their friendship gave me a sense of comfort, and was like an anchor of safety in the emotionally wrecking journey of the therapy sessions, Natalia’s disturbing speeches, and all the corporate crap. It was just necessary to shutter that seemingly working relationship, and Del Rosso did it with outstanding artistry. By making Tess do every mistake she worked on fixing in others.

“I know a thousand Jacksons” says Tess, and everyone in the audience puts an expression of solidarity on their face. We all know Jackson, we’ve met him hundreds of times. How does he manage to get away every single time then? How is he still a successful CEO of a tech company; someone’s boyfriend, husband, or a father; someone’s friend or a neighbour? And if we all feel about him the way Tess does, how does he succeed? The play doesn’t give us a hopeful outlook or a moral lesson. It almost feels like despite the main character’s powerful display of female rage, which is something I’d love to see more of in popular media, it is Jackson’s monologue that is the triumph. We can firmly believe that we deserve better than him, and that we are so much more than he could ever be, but somehow he still manages to figure out any algorithm that prevents him from getting what he wants. He knows exactly what values to put into equations that lead to a fast track to anything he lays his eyes on. This is what frustrates in that story.

The Clockwork Pink

If Jackson actually learnt about empathy, active listening, consent, and what makes a good apology, can we say he improved? Even if he doesn’t believe in it and uses this knowledge merely as a tool, he still shows desirable behaviours. And behaviour is the most objective way of measuring one’s psyche. Can we programme a good person? Is that concept ethically correct?

Tess’s burning enthusiasm about The Gradient quickly evaporates in order to leave space for the growing disagreement and doubt. She realises that math and science will only take you so far, but it is were conflicting interests of stakeholders, power plays, and human flaws come together that the real innovation takes place. The numbers don’t lie, unlike the patients. Natalia, just like her new employee, believed in the algorithm, but what makes her different from Tess is that she did not try to change the game and learnt to play by its rules instead. She certainly excelled in that art. She is actually a mirrored image of Jackson. She makes the algorithm, he is the one to crack it. He plays her game, but it was never hers to begin with. Tess wanted to kill them both, but they were the ones to kill her.

One of the most important monologues of Jackson was the one about a stir fry of sorry’s, however foolish it might have seemed. What he actually did was to accidentally (or perhaps very cunningly) reveal what The Gradient really is about – mass producing apologies and thoughtless patterns of behaviours. It is nothing more or less than cooking a big, greasy stir fry that will satisfy you for a day, and then give you a terrible food poisoning the day after. Even though the therapy was tailored to each individual, at the end of the day it was the same process for everyone. It was demonstrated in a spectacular way through having one actor play all Tess’s patients, and rapidly switch between them without any additional cues other than the different mannerisms, speech patterns, and body language. It was an impressive, attention-grabbing move that ultimately lead the audience to notice how little room for different shades of people The Gradient had to offer.

Some of the men, however, seemed to have actually realised their flaws. Their egotistical façade was broken through. But what is the next step? They did not work through their issues that let them to become insecure, self-absorbed, and so far detached from their own emotionality. Continuing their journey in a meaningful way after the release was, as Natalia said, a minority that reaches the media attention. For the rest of the wicked, all there was left was to leave a positive comment for the facility and go on with their lives with some more clearance, and a lot more confusion.

Crime and Punishment

I have hopefully showed by now that The Gradient talks about much more than sexual assault. It does, however, talk about sexual assault as well, and that topic should never be summarised with merely a meaningful moment of silence. We should speak about it, loud and clear, with confidence. I know it feels just right that the (female!) CEO of a facility that rehabilitates people charged with sexual misconduct is a prime example of victim blaming, but If there is one action to take after having watched the play, it is to make sure this is not what actually awaits us in the not-so-distant future.

“She remembers it every day. She thinks about it every time she has sex”.

Jackson, after hearing that, says: “I’m sure she’s moved on”. I, in my hopeful naivety, want to believe that he denies the truth because otherwise he could never look himself in the eyes again. That he tells Tess what his ex-girlfriend should hear because he would literally burn under her hollow look. That he was so happy and relieved after because the weight of his guilt has slightly lifted off his shoulders. That the image of a woman that accepts her fate instead of enjoying her first sexual experience is so engraved in his mind he can’t sleep at night. That this is the reason he was looking at his generic picture on the wall for hours. That’s the least Jackson’s ex-girlfriend and all the other women deserve. That those who shaped our understanding of sex as something to be ashamed of and to endure like a duty, at least feel bad about themselves. If not all the time, then at least half of the time. Or sometimes. We want to believe that them saying “I’m sorry you overreacted” or calling us a slut is the only way they can express that feeling. “I’m relieved”, says Jackson after hearing that the woman whose security he took away is doing fine. And yes, she is fine despite him, not without him. Relief is not meant for her.

The expression on Jackson’s face changed after Tess’s final outburst. Is it a look of remorse? Was he actually touched and at least felt bad for a moment? Would her words leave a mark on him? His response, if not prevented by the supervisor, could be a start to a dialogue. The only genuine and impactful dialogue in his therapeutic process, if not in the whole play. It takes courage to face your emotions and shout them out in someone’s face. Jackson’s ex-girlfriend would probably not have that courage. Luckily, Tess decided to not merely listen an apology not meant for her, but to also give a response in another woman’s name. Sadly, the algorithm did not teach him how to receive it and take something away from it.

Let Him Who Is Without Sin Cast The First Stone

The biggest question the play raises is “how are YOU fucked up?”. It is not just a funny gag or a way to engage the audience. It really is the essence of “The Gradient”. Nobody is black or white. We all are in the grey area, in one way or another. Natalia addressing us, the audience, is not a wink. It’s a slap in the face. And we take it with a laugh, but really we should cry. We applaud ourselves for not being rapists, but really we should whip our own backs for everything we are instead. Liars. Cheaters. Narcissists. Slaves of our own emotions. Jealous. Angry. Greedy. Full of self-pity.

What would be your score on empathy? How about introspection or potential for growth? We can only hope we’d get fast-tracked. We say we want to change the world, like Tess, but we have one true reason behind, just like she did – to achieve something; to feel fulfilled; better than everyone else. And what is a better way to feel good about yourself than to watch a play about evil people struggle to become any less insufferable? But we cannot just turn a blind eye on how the world has changed Tess. How it turned her from an ambitious, prosperous woman who talks to mice into someone capable of violence, struggling to maintain her own relationships, misinterpreting her coworker’s signals and failing to take responsibility for it. Her moral collapse is a more disheartening view than any of the men she gave therapy to. What is the worst part of it all, is that her biggest sin was not giving up in the fight against the senseless rules of the system governing The Gradient. Against the reality. She could have instead kept stacking clay until it falls, and then begin again. This is the only sin, however, that allows you to take the first stone and cast it. Cast it at a mirror that hangs in front of your face and shutter it to see what shade of grey you are."

Review written by Julia Kubiak, a dedicated Activities Committee member who organised this thrilling excursion to watch "The Gradient" by Homerostheater for WILDe's Members!

You can find Julia on instagram: @toreisvogel